People with non-cancerous long-term health conditions

What the evidence shows

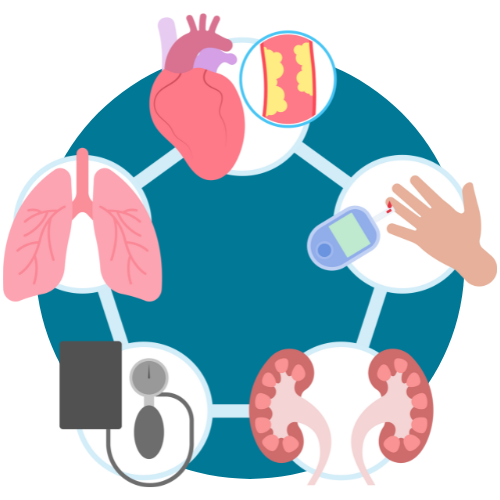

Approximately 75% of end-of-life patients will die from non-malignant conditions (including end-stage renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease). Yet despite this, there is evidence of a range of inequalities in end-of-life care, demonstrated in access to services, quality of care, and the overall experience for patients and their families.

Palliative care continues to be more often linked to the care of people with cancer, both by the public and wider health and care workforce. Historically, this may have been because the symptoms and progression of cancer are often more predictable compared to non-cancerous chronic illnesses. With cancer, there is typically a period where daily function is maintained, followed by a potentially rapid decline. For people living with chronic non-cancerous illnesses there is typically a slower, more variable decline over many years, with periods of symptom flare-ups and recovery. This difference matters because people with non-cancer life-limiting illnesses often face similar levels of symptoms and care needs to cancer patients, but they are less likely to receive timely palliative care services. Also, the varied nature of these illnesses means that patients and their families have diverse and changing needs.

There are also associations with social determinants of health in relation to non-malignant conditions, linked to challenges related to socioeconomic status, geographic location, or cultural background, which influence individuals' access to, and experience of, end-of-life care. These factors can affect decision-making, care preferences, and the ability to navigate healthcare systems.

The non-linear progression of disease can delay or prevent discussions about end-of-life care preferences. This can result in interventions at end of life that may not align with patient wishes, contributing to poorer end-of-life experiences for the individual and their loved ones.

What Kirklees organisations told us

Although the palliative care pathway is most straightforward for cancer patients, local hospitals are now doing more advance care planning for patients with other life-limiting health conditions, supported by dedicated hospice staff, and The Kirkwood has seen an increase in their proportion of non-cancer patients. As the service expands to incorporate other health conditions, this will naturally change the demographic profile of hospice patients, where certain health conditions are more strongly associated with people from a non-White background or people living in more deprived areas.

Other topics covered during discussions included:

Referral pathway

If hospice referrals could be more automated (for example, triggered when dialysis treatment ends), this would reduce some of the inequalities seen in hospice referrals. Feedback suggests there may be a lack of general information about support available for people with non-malignant life-limiting conditions.

By putting the referral process into the hands of patients and relatives, that will help to reduce some of the inequity around, meaning that it's not just based on healthcare knowledge about what's happening... it's more general than that, and at an earlier stage.

Care planning

It's much easier to look after somebody at the end-of-life if services have had contact with them leading up to that point. When advance care planning is done well, it's allowed to adapt over time, building on things that have been planned before.

If we've built up a rapport with somebody, it's much easier... they have the confidence that what we're telling them is the correct management plan.

Connected systems

Early conversations about future patient needs can help with seamless transition between services. If we're developing systems, providers need to work in collaboration to ensure the impacts on other parts of the system are accounted for. Having people's health and care records in one place is helpful.

An awful lot of people get good end-of-life care experiences in Kirklees, and that is down to lots of different services and when services work well together.

Individual choice

One model of care doesn't fit everybody. We shouldn't deny someone the opportunity to go into hospital for surgery, but make them aware of the options, rather than going to hospital being the automatic thing. Self-referrals to The Kirkwood are increasing, demonstrating an element of individual choice.

We've doubled the number of people who self-referred, which is good. We've had a higher number of people from the most deprived 20% of Kirklees...And we've had more non cancer referrals as well.

Primary care

There is lots of work going on within primary care around early identification of patients, although there is still inequity in palliative care referral rates across the district.

Service design

It is important to have patient and public involvement in planning and delivering care services. Referral data at GP practice level is also being used to aid service design. Where there is a requirement to demonstrate impact, it is often easier to go for the simpler, higher volume cases, rather than dealing with complex cases and people with chaotic lifestyles which are more resource-intensive but are lower in number.

It's just about being creative with making our services fit the demographic of the wider community.

Volunteer support

Volunteers could be used for practical things like collecting medicines or being on the other end of a phone for advice. Having more capacity to support carers - for example, to provide washing, shopping, cleaning, or extend the night sitting service - would enable the carer to get some rest at home. Designated end-of-life social prescribers could connect people to volunteer support. The use of a 'death doula' was suggested - this is a companion to support people through the dying process, emotionally, spiritually and practically.

Workforce

It would help if the workforce reflected the demographics of the patient population. Also, training staff to initiate conversations about dying and end-of-life care, without assuming someone else in a different service has already had those conversations.

Bereavement

Bereavement counselling services are seeing an increasing number of people. Anyone identified as being at risk of a complicated bereavement reaction will be offered counselling at 6 weeks post death.

COVID impact

Since COVID, people seem to be less able to cope with losses and have raised expectations about healthcare. This may relate to control issues, as people didn't have control during COVID and are now trying to exert some control back.

Recommendations

- Improve the available information about referral pathways

- Utilise existing relationships with healthcare professionals to carry out advance care planning

- Place a greater emphasis on early identification of opportunities for introducing palliative care

- Increase the use of volunteers or community support to reduce the burden on carers

- Train staff to ensure people are able to die with dignity